My previous blog post, “Denying Racism is the new Racism” (July 28, 2017) generated a lot of commentary. Most of it supported the central theme of the post, that racism, while not as prevalent in American culture as it once was, is still with us. Today racism often appears in more subtle forms, such as in the denial of its existence. I find such views almost unbelievable considering America’s painful history in matters of racial injustice, history that is readily accessible to anyone who wants to know about it. I responded individually to several of the questions posed in response to my blog, but since several of the questions followed a similar pattern, I thought it would be helpful to answer them all with a deeper dive into the topic and to share my response in an additional blog post.

My previous blog post, “Denying Racism is the new Racism” (July 28, 2017) generated a lot of commentary. Most of it supported the central theme of the post, that racism, while not as prevalent in American culture as it once was, is still with us. Today racism often appears in more subtle forms, such as in the denial of its existence. I find such views almost unbelievable considering America’s painful history in matters of racial injustice, history that is readily accessible to anyone who wants to know about it. I responded individually to several of the questions posed in response to my blog, but since several of the questions followed a similar pattern, I thought it would be helpful to answer them all with a deeper dive into the topic and to share my response in an additional blog post.

I am the son of an immigrant, a black man from the Caribbean Island of Trinidad who came to this country 100 years ago to seek a better life. He found it and earned his citizenship as a soldier on the battlefields of World War One. Despite the racism and physical violence he experienced in the U.S. as both an immigrant and a person of color, my father found the opportunity he sought and was always happy he came to the U.S. I tell his amazing story in my novel, A Place near the Front. I share his views and am also happy to be an American. Although I grew up in the late 1930s and 1940s when racism and discrimination was still rampant, and there were many places where people of color could not live, work and in some cases vote, we have made much civil rights progress since those days. In my view, this is the country in which opportunities are best for me and my family to live full, free and complete lives.

In recognizing the many great attributes of American life, I don’t close my eyes to the nation’s two original sins, how it was built on land stolen from native Americans and built on the backs of slave labor. Despite the long-lasting impact of those indelible blemishes, America has come a long way toward making itself a land of opportunity for all. But as I pointed out in the previous blog, for every step forward we make in advancing the freedoms of one segment of America, there is another segment that may see such gains as their loss. When one group of citizens gains the right to vote, another may have the feeling that their vote has been diluted and now doesn’t count for as much. Or when one group gains access to improved schools, another may lament their reduced access if the overall school size does not increase.

When one segment of American society perceives it is losing ground in the public arena, it usually pushes back. This explains why advances against racism and intolerance are often followed by unexpected reversals. I discussed those kinds of reversals in my previous blog. But one of the most recent and subtle forms of pushback is the denial of racism itself. While some of this denial seems to be the self-serving rhetoric of those unwilling to acknowledge how they, as a privileged class may have, for generations, benefited from the repression of other classes, I will now respond to a few of the questions posed in rebuttal to my blog.

Reader rebuttal comment #1 – “Everybody is sick and tired of the same old crap! Get past it!”

My Response

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could get past this crap. But we can’t, because in case you hadn’t heard, hate crimes are on the increase in the U.S. and we’re not talking about ancient history. This is happening today! The FBI reported a 15% increase in hate crimes in 2015 over the previous year, and in 2016 and 2017 increases are even higher. The nooses I talk about in my post were displayed within the last few months. With the alarming recent increases in hate crimes, these shameful symbols have to be taken seriously. I’ll bet you wouldn’t get over it so quickly if your child was the college student that was being threatened with lynching.

Reader rebuttal comment #2 – “The people screaming racism are just as racist as the people they are accusing”

My Response

The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously once said: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” Hard data on hate crimes presented by the FBI cannot be placed on the same level as crackpot opinions shared in internet videos. The facts about racism cannot be denied, and to ignore them would be irresponsible. Your denial of them is a great example of my post: “Denying Racism is the New Racism.”

Reader rebuttal comment #3 – “Many groups have faced discrimination. why do blacks think they are so special?”

My Response

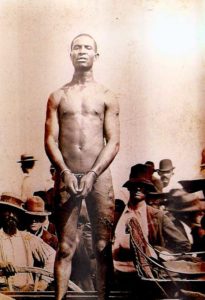

It is true that many groups, especially immigrants, have been subjected to cruel and unlawful treatment that America should have never allowed. But it is absurd to deny the uniqueness of discrimination against African-Americans, how we were owned as property and used as beasts of burden and breeding machines. No other ethnic or racial group has been subjected to this kind of brutality other than native Americans.

It is true that many groups, especially immigrants, have been subjected to cruel and unlawful treatment that America should have never allowed. But it is absurd to deny the uniqueness of discrimination against African-Americans, how we were owned as property and used as beasts of burden and breeding machines. No other ethnic or racial group has been subjected to this kind of brutality other than native Americans.

Reader rebuttal comment #4 – “Black on black crime runs rampant in many U.S. cities. How can you complain about racism when you do so much violence to each other?”

My Response

Black on black violence is a shameful situation in America and cannot be excused or tolerated no matter the reason. Blacks don’t live in substandard ghettos by choice, but are there because there are no opportunities to live anywhere else. And experts in human behavior have long known that when a disadvantaged group is penned up in substandard living conditions and denied the educational and job opportunities necessary to improve their lot, they often take out their frustrations in violence against each other. This doesn’t excuse the behavior, but any group so restricted is likely to behave in the same manner. Elimination of racist barriers to education and employment will go a long way to reduce imprisonment in violent inner city situations.

Reader rebuttal comment #5 – “Nothing prevents people from changing and improving their living conditions. Why don’t black people do this and stop complaining about racism?”

My Response

Finding and accumulating the resources and assets necessary to overcome longstanding inequities created by racism, and to lift oneself into a higher standard of living is always possible, but to do so can require exceptional skills and strengths. It would be great if every person of color living in substandard conditions had the exceptional resources required to pull off such an escape. But that is not realistic, and shouldn’t have to be. One shouldn’t have to possess exceptional skills in order to live a normal life. In mainstream America, citizens are not expected to be exceptional to live a fulfilled life and be a productive member of the American society. Expectations of Americans of color should be no higher.