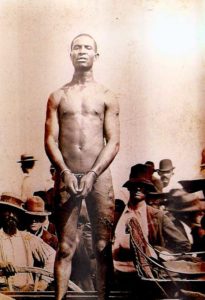

Wilbur Little was one of the 200,000 black soldiers who served the U.S. in World War One. The day he returned to Blakely, Georgia in 1919, he was met at the train station by a group of white men who forced him to take off his uniform. A few days later when he was again seen wearing the uniform, a white mob lynched him. Little’s murder and that of other returning black soldiers, many also in uniform, sent out a clear message that the sacrifices made by African Americans for the cause of liberty in Europe had not lead to racial equality in America.

Wilbur Little was one of the 200,000 black soldiers who served the U.S. in World War One. The day he returned to Blakely, Georgia in 1919, he was met at the train station by a group of white men who forced him to take off his uniform. A few days later when he was again seen wearing the uniform, a white mob lynched him. Little’s murder and that of other returning black soldiers, many also in uniform, sent out a clear message that the sacrifices made by African Americans for the cause of liberty in Europe had not lead to racial equality in America.

Racial tensions in the U.S. increased dramatically in the months following the war, and blacks had to fight, quite literally, for their survival. The massive migration of southern blacks to northern cities and the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan contributed to the unrest. Black social consciousness was increasing, urged on by men like Marcus Garvey with his “back to Africa” movement, and Father Devine who was calling for black pride. Military service had given blacks a new sense of confidence and political awareness and they were beginning to demand their rights.

The return of these newly-empowered soldiers spawned a nationwide surge of violence against blacks. Race riots erupted in several cities, the worst in Washington, D.C. and Chicago. In 1919, whites in Elaine, Arkansas massacred hundreds of black people in retaliation for the efforts of sharecroppers to organize themselves. The number of lynchings in the U.S. increased from sixty-four in 1918 to eighty-three in 1919. For African Americans, the end of the war meant anything but peace. Poet and author James Weldon Johnson characterized the bloody summer of 1919 as the Red Summer.

Lynching had long been deeply embedded into America’s racial psyche. The end of World War One saw this deadly form of vigilante “justice” reinvigorated into a modern symbol of enduring white power and superiority. Lynching was aimed at expelling blackness from the white community and reaffirming the purity of the white race. It was often targeted at the mythical “black beast rapist” who embodied white fears of black hypersexual animalism. Throughout the Red Summer of 1919, lynchings and their aftereffects followed a similar pattern:

Lynching had long been deeply embedded into America’s racial psyche. The end of World War One saw this deadly form of vigilante “justice” reinvigorated into a modern symbol of enduring white power and superiority. Lynching was aimed at expelling blackness from the white community and reaffirming the purity of the white race. It was often targeted at the mythical “black beast rapist” who embodied white fears of black hypersexual animalism. Throughout the Red Summer of 1919, lynchings and their aftereffects followed a similar pattern:

- A black person, usually a man, is accused of some heinous crime, such as raping a white woman

- The accusation is assumed to be true

- The white mob lynches the accused, then marches into the black areas of the town destroying property and beating up or killing residents.

This pattern of terrorism and intimidation was repeated again and again during the Red Summer of 1919 when black communities and economic centers were burned to the ground. Often the accused was charged with nothing more than showing defiance or arrogance by wearing a U.S. military uniform.

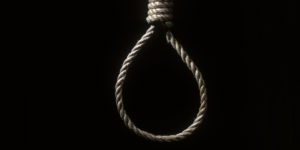

In the succeeding 100 years we like to think that such days are long behind us, and that we will never again see the abuses of African Americans described in my historical novel, A Place near the Front. But nooses found recently at several locations in the National Mall and in other spots around the country remind us that we may not have progressed as much as we think.

As Lonnie Bunch writes in the New York Times: “The person who recently left a noose at the National Museum of African American History and Culture clearly intended to intimidate, by deploying one of the most feared symbols in American racial history. Instead, the vandal unintentionally offered a contemporary reminder of one theme of the black experience in America: We continue to believe in the potential of a country that has not always believed in us, and we do this against incredible odds.”

“The noose — the second of three left on the National Mall in recent weeks — was found late in May in an exhibition that chronicles America’s evolution from the era of Jim Crow through the civil rights movement. Visitors discovered it on the floor in front of a display of artifacts from the Ku Klux Klan, as well as objects belonging to African-American soldiers who fought during World War I. Though these soldiers fought for democracy abroad, they found little when they returned home.”

“So, what does it mean,”Mr. Bunche asks, “to have found three nooses on Smithsonian grounds in 2017? A noose inside a Missouri high school? A noose on the campus of Duke University? Another at American University?”

“I would argue, ”he contends, “that it answers a naïve and dangerous question that I hear too often: Why can’t African-Americans get over past discrimination?”

“The answer is that discrimination is not confined to the past. Nor is the African-American commitment to American ideals in the face of discrimination and hate.”

“The exhibitions inside the museum combine to form a narrative of a people who refused to be broken by hatred and who have always found ways to prod America to be truer to the ideals of its founders.”