On the night of May 14, 1918, Private Henry Johnson stood guard at Outpost 20 of the Argonne Forest in France’s Champaign region. Shortly after midnight, he thought he heard the the sounds of someone cutting through the barbed wire in the “no-man’s land” that separated the American and German front lines. German snipers then began firing on Johnson and another soldier, Needham Roberts, who was on guard duty with him.

On the night of May 14, 1918, Private Henry Johnson stood guard at Outpost 20 of the Argonne Forest in France’s Champaign region. Shortly after midnight, he thought he heard the the sounds of someone cutting through the barbed wire in the “no-man’s land” that separated the American and German front lines. German snipers then began firing on Johnson and another soldier, Needham Roberts, who was on guard duty with him.

“There isn’t so much to tell,” Johnson told an interviewer in New York after the war when he described what happened after the German snipers opened fire.

“…I began to get ready. They’d a box of hand grenades there and I took them out of the box and laid them all in a row where they would be handy… the snippin’ and clippin’ of the wires sounded near so I let go with a hand grenade. There was a yell from a lot of surprised Dutchmen and then they started firing. … A German grenade got Needham in the arm and through the hip. He was too badly wounded to do any fighting so I told him to lie in the trench and hand me up the grenades. Keep your nerve I told him. All the Dutchmen in the woods are at us but keep cool and we’ll lick ’em. … Some of the shots got me. One clipped my head, another my lip, another my hand, some in my side, and one smashed my left foot so bad that I have a silver plate holding it up now. The Germans came from all sides. Roberts kept handing me the grenades and I kept throwing them, and the Dutchmen kept squealing but jes’ the same, they kept comin’ on. When the grenades were all gone I started in with my rifle.”

Johnson was using the French rifle he’d been given after being placed under the French Army’s command. When he tried to load an American magazine, the French rifle jammed.

“There was nothing to do but use my rifle as a club and jump into them. I banged them on the dome and the side and everywhere I could land until the butt of my rifle busted. One of the Germans hollered, ‘Rush him, Rush him.’ I decided to do some rushing myself. I grabbed my French bolo knife and slashed in a million directions. … They knocked me around considerable and whanged me on the head, but I always managed to get back on my feet. There was one guy that bothered me. He climbed on my back and I had some job shaking him off and pitching him over my head. Then I stuck him in the ribs with the bolo. I stuck one guy in the stomach and he yelled in good New York talk: That black ——— got me. I was still banging them when my crowd came up and saved me and beat the Germans off.”

“There was nothing to do but use my rifle as a club and jump into them. I banged them on the dome and the side and everywhere I could land until the butt of my rifle busted. One of the Germans hollered, ‘Rush him, Rush him.’ I decided to do some rushing myself. I grabbed my French bolo knife and slashed in a million directions. … They knocked me around considerable and whanged me on the head, but I always managed to get back on my feet. There was one guy that bothered me. He climbed on my back and I had some job shaking him off and pitching him over my head. Then I stuck him in the ribs with the bolo. I stuck one guy in the stomach and he yelled in good New York talk: That black ——— got me. I was still banging them when my crowd came up and saved me and beat the Germans off.”

The five foot four inch Johnson calmly concluded his account of the battle: “That’s about all. There wasn’t so much to it.”

Later that year, after the war ended, the “New York World” and “The Saturday Evening Post” described how Johnson, despite receiving 21 wounds in hand-to-hand combat, single-handedly killed four Germans and wounded as many as twenty more.

Despite a few early accolades, the U.S. military didn’t think there was much to Johnson’s heroism and did nothing to formally recognize it. Although the French celebrated his bravery, Johnson had nothing to show from his own government, not even a Purple Heart for the serious wounds he sustained that kept him hospitalized for months. Because the army kept no record of Johnson’s injuries, he was ineligible for disability benefits after his discharge.

Five years after he returned from the war, Johnson, unable to work because of his injuries, separated from his wife. Alone, he spent his last years in poverty and alcoholism before dying, in obscurity, at a veteran’s hospital in 1929 at the age of 36.

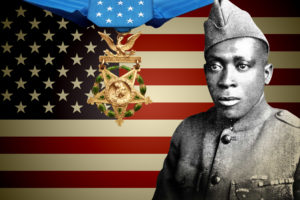

Today, many wonder how such an injustice could possibly have occurred. But in 1918, racism against African Americans was common among white American troops throughout the U.S. military chain of command. The French, however, had no such problems with American black troops. Johnson was recognized by the French with a Croix de Guerre with star and bronze palm, and was the first American soldier in World War I to receive that honor. From 1919 on, Henry Johnson’s story has been part of wider consideration of treatment of African Americans in the Great War. There was a long struggle to achieve awards for him from the U.S. military. He was finally awarded the Purple Heart in 1996. In 2002, the U.S. military awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross. Previous efforts to secure the Medal of Honor failed, but in 2015, ninety-seven years after his heroism, he was finally honored with the award by President Obama.