I never got to see Denzel Washington in The Iceman Cometh during its 2018 run, the fourth Broadway iteration of the Eugene O’Neill classic. But that’s ok. Long before the play began its first run in the1940’s, the kids on my Harlem block and I enjoyed regular performances of our own real-life iceman, the guy who delivered ice for our old-fashioned ice-boxes. A big powerful brother, always wearing the same beat-up fedora and leather apron, he was an important guy in our neighborhood, especially in the summer months. In the winter, if he didn’t show up and someone ran out of ice, food could always be left outside on a window sill for a day or two. But if he didn’t make his deliveries on one of those stifling hot summer days when even a slight breeze was hard to come by, a whole lot of food would go to waste.

I never got to see Denzel Washington in The Iceman Cometh during its 2018 run, the fourth Broadway iteration of the Eugene O’Neill classic. But that’s ok. Long before the play began its first run in the1940’s, the kids on my Harlem block and I enjoyed regular performances of our own real-life iceman, the guy who delivered ice for our old-fashioned ice-boxes. A big powerful brother, always wearing the same beat-up fedora and leather apron, he was an important guy in our neighborhood, especially in the summer months. In the winter, if he didn’t show up and someone ran out of ice, food could always be left outside on a window sill for a day or two. But if he didn’t make his deliveries on one of those stifling hot summer days when even a slight breeze was hard to come by, a whole lot of food would go to waste.

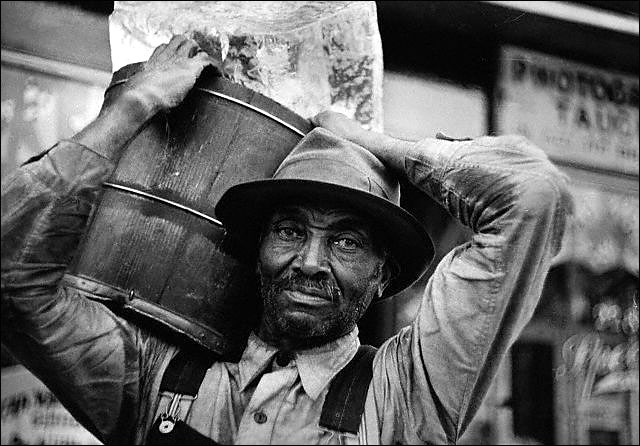

Iceman was not only his job title, but it was also the name we called him. On summer mornings when school was out, he would be met by the same pack of noisy kids who followed him as he worked. We were always excited to see the big man and his horse-drawn wagon, and always looked forward to the cooling pieces of ice we knew he would give us.

Every other day, Iceman would stop his wagon a few doors down from the entrance to the apartment building my family lived in on 116th Street between Seventh and Lenox Avenues. He would scan the nearby apartment windows for small signs on which one of the amounts: 10c, 15c, or 20c were printed. A sign in the window told him the size of the ice block he should bring up to the apartment. While his horse stood motionless before us, occasionally flicking his tail or his ears, or magically shaking whole sections of his skin to shoo away pesky flies, the big man would pull the blanket off the big slabs of ice in the back of his wagon and begin chipping out blocks with his tongs and ice-pick. To our delight, he would toss us the ice debris produced as he carved out the blocks.

Every other day, Iceman would stop his wagon a few doors down from the entrance to the apartment building my family lived in on 116th Street between Seventh and Lenox Avenues. He would scan the nearby apartment windows for small signs on which one of the amounts: 10c, 15c, or 20c were printed. A sign in the window told him the size of the ice block he should bring up to the apartment. While his horse stood motionless before us, occasionally flicking his tail or his ears, or magically shaking whole sections of his skin to shoo away pesky flies, the big man would pull the blanket off the big slabs of ice in the back of his wagon and begin chipping out blocks with his tongs and ice-pick. To our delight, he would toss us the ice debris produced as he carved out the blocks.

“Honey, you don’t know where that ice has been,” my mother would often warn me about eating anything from Iceman’s dilapidated old wagon. But I didn’t care about any germs. On a hot summer day, Iceman’s chips were like manna from heaven.

When an order was ready, Iceman would throw it up onto his shoulder in a wood basket. With a bunch of us tagging along behind him, he would trudge up several flights of stairs to put the ice in the customer’s box. When all the orders were filled at this location, he would pull his wagon a few buildings further down the street and repeat the process, now joined by new kids, with a few from the previous stops still tagging along.

Iceman never said much and smiled only occasionally. But his hard work and patience with us told us everything we needed to know about him. His strength, ice tongs, ice pick, and horse earned him such a high cool factor, he was like a black Lone Ranger to us, a real super-hero. In those days, we latched on to all the role-models we could get.

By the late ‘40s, my family and our neighbors had moved from the icebox to the refrigerator era, and many had moved to new neighborhoods. Just like that, the tiny wood boxes disappeared, and we didn’t see Iceman anymore.

I didn’t think about him again until recently. I found myself caught up in a flashback of recollections about him when I saw an antique icebox on display as a novelty in an upscale Detroit coffee shop where gourmet lattes can run upward of $10. As I paid for my mocha with the new app on my smartphone, the odd juxtaposition of the old and the new unleashed a sudden flood of memories, a jolting reminder of how much the world had changed in the blink of an eye since the days when we chased Iceman and begged for treats.