The heavyweight fights between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling in the 1930s were two of the most anxiously anticipated and highly viewed events in the sports history. In time, the Brown Bomber would become the world’s first black heavyweight boxing champion since Jack Johnson in the early 1900s. And in Nazi Germany, Max Schmelling, the former world champion, was touted as an example of the Aryan racial superiority. In the run-up to the World War Two, their matches came to be seen as representative of struggles between American democracy and Nazi fascism.

The heavyweight fights between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling in the 1930s were two of the most anxiously anticipated and highly viewed events in the sports history. In time, the Brown Bomber would become the world’s first black heavyweight boxing champion since Jack Johnson in the early 1900s. And in Nazi Germany, Max Schmelling, the former world champion, was touted as an example of the Aryan racial superiority. In the run-up to the World War Two, their matches came to be seen as representative of struggles between American democracy and Nazi fascism.

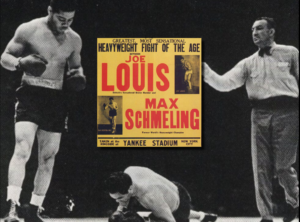

In the first fight on June 19, 1936, the German fighter defeated Louis by way of a 12th-round knockout at Yankee Stadium. The loss devastated Louis but also motivated him to further refine his skills so that he could seek vengeance at a later date. International events leading up to the rematch added an air of mystique, with tensions between the United States and Nazi Germany growing more strained each day. Further, the U.S. was still recovering from the Great Depression and the bout between the boxing giants served as a necessary distraction.

When the two met for their return match in 1938, Louis had already beaten James Braddock for the heavyweight championship, but the Schmeling defeat still rankled him and he stated to the press: “I will not consider myself champion until I defeat him.” When they stepped into the ring for a second time, Louis was not just a symbol of black pride but also America’s champion against a formidable foreign power. He was patronizingly referred to by many white Americans as: “A credit to his race.” Schmeling was also revered in Germany but struggled with the responsibility placed on him by the Nazis.

When the two met for their return match in 1938, Louis had already beaten James Braddock for the heavyweight championship, but the Schmeling defeat still rankled him and he stated to the press: “I will not consider myself champion until I defeat him.” When they stepped into the ring for a second time, Louis was not just a symbol of black pride but also America’s champion against a formidable foreign power. He was patronizingly referred to by many white Americans as: “A credit to his race.” Schmeling was also revered in Germany but struggled with the responsibility placed on him by the Nazis.

Despite the public’s perception, Schmeling never once claimed allegiance to Hitler or Nazism and even dared to have a Jewish manager in his corner. Although proud of his German nationality, he denied the Nazi claims of racial superiority: “I am a fighter, not a politician. I am no superman in any way.” In a dangerous political gamble, he refused the “Dagger of Honor” award offered by Adolf Hitler. In fact, Schmeling had been urged by his friend and legendary ex-champion Jack Dempsey to defect and declare American citizenship. To the German fighter’s dismay, the Nazi propaganda machine predicted that Schmeling would soundly defeat Louis thereby again reaffirming Aryan superiority.

But the second fight was a completely different story. The hard-punching and determined Louis attacked Schmeling from the opening bell with punishing accuracy, delivering devastating blows that caused the German to wince audibly and hang on to the ropes to keep his footing. Schmeling had been floored three times when the referee stopped the fight in two minutes and four seconds of the first round calling it a technical knockout.

Reaction in the mainstream American press, while positive toward Louis, reflected the implicit racism in the United States at the time. Lewis F. Atchison of The Washington Post began his story: “Joe Louis, the lethargic, chicken-eating young colored boy, reverted to his dreaded role of the ‘brown bomber’ tonight”; Henry McLemore of the United Press called Louis “a jungle man, completely primitive as any savage, out to destroy the thing he hates.”

Louis went on to continue a long and storied boxing career eventually becoming national hero. When questioned by prominent blacks about whether African Americans should serve against the Axis nations in the segregated U.S. Armed Forces, Louis said, “There are a lot of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain’t gonna fix them.” He would go on and serve the United States Army during World War II, mostly visiting soldiers in Europe to provide them with motivational speeches and with boxing exhibitions. He kept defending the world heavyweight title until 1949, making twenty five consecutive title defenses – still a world record among all weight divisions.

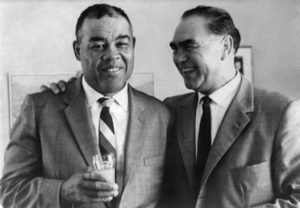

Sadly, Joe Louis fell on hard times after his boxing career and was doggedly pursued by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service for what they claimed were unpaid income taxes. The IRS never counted, against those alleged back taxes, the many charity fights he fought while in the army to entertain U.S. troops. Schmeling despite falling out of favor with the Nazis went on to have a long and successful business career.

Sadly, Joe Louis fell on hard times after his boxing career and was doggedly pursued by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service for what they claimed were unpaid income taxes. The IRS never counted, against those alleged back taxes, the many charity fights he fought while in the army to entertain U.S. troops. Schmeling despite falling out of favor with the Nazis went on to have a long and successful business career.

The two boxers developed a friendship outside the ring, which endured until Louis’ death on April 12, 1981. Toward the end of his live, Louis got a job as a greeter at a Las Vegas casino, and Schmeling flew in to visit him every year. Schmeling reportedly also sent Louis money in Louis’ later years and covered a part of the costs of Louis’ funeral, at which he was a pallbearer. Schmeling died 24 years later on February 2, 2005 at the age of 99.